|

| Sir Christopher Cradock, KCVO, CB, SGM |

Christopher George Francis Maurice Cradock was born on 2 July 1862 at Hartford, Yorkshire, the fourth son of Christopher Cradock and his wife Georgina.

|

| Cdr Cradock and dogs |

Cradock wrote two minor books; Sporting Notes in the Far East (1889) and Wrinkles in Seamanship (1894), but it was his Whispers from the Fleet (1907) that outlines his naval philosophy. Addressed to officers entering upon their careers, he throws scorn on the civilians driving the naval arms race, who were 'for ever writing to the newspapers to prove... that unless we do something we shall in ten years time be seven-eighths of a battleship behind the combined navies of the world'. As the DNB put it, 'to him the navy was not a collection of ships, but a community of men with high purpose'.

|

| Wreck of the SS Delhi |

In 1913 he took command of the North American and West Indies Station. At the outbreak of war in August 1914, he had responsibility for an area from Canada to Brazil and the immediate duty of finding and destroying the German commerce-raiding cruisers, which were operating independently in the North and South Atlantics. After satisfying himself that the North Atlantic trade routes were safe, Cradock joined the South Atlantic Squadron and raised his flag in HMS Good Hope, with the aim of sinking the cruiser Dresden.

|

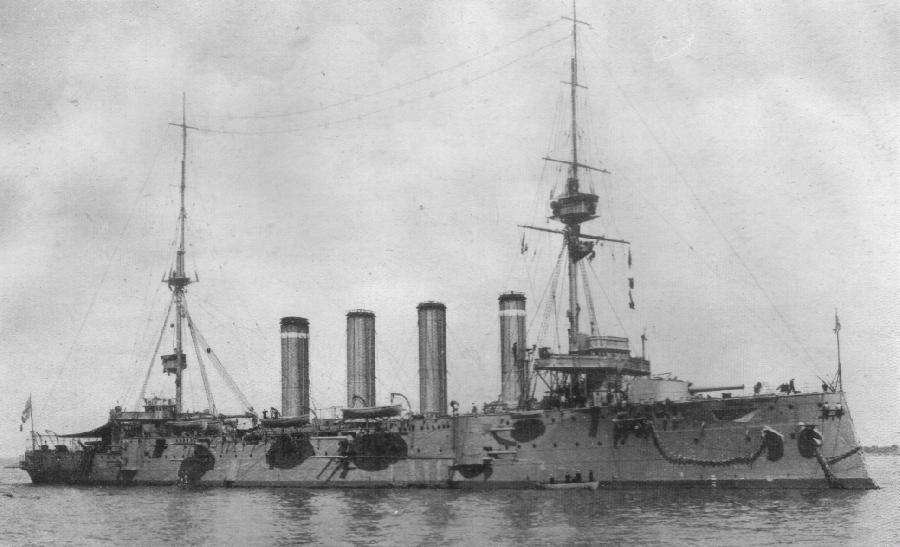

| HMS Good Hope |

While cruising off the east coast of South America, Cradock received information from the Admiralty that Admiral von Spee's German East Asia Squadron was moving eastwards across the Pacific, with the Falkland Islands coaling station as its presumed destination, and that Cradock should 'be prepared to meet them in company'.

Cradock's force consisted of obsolete and under-armed vessels, crewed by naval reservists called up a few months earlier. These were the armoured cruisers HMS Good Hope and HMS Monmouth, the modern light cruiser HMS Glasgow, three other light cruisers, a converted liner—HMS Otranto—and two other armed merchantmen. The armoured cruiser HMS Defence, had been due to join the squadron, but this ship was diverted, and the pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Canopus took its place. Canopus had been due to be scrapped, but was reprieved on the outbreak of war: although designed to make 18.5 knots, she could barely manage 12 - half the speed of the rest of the squadron. The Admiralty refused Craddock's request for further reinforcements.

After formally protesting his orders, Craddock split his forces in two; half to patrol the east coast of South America and the other the west coast. Good Hope, Glasgow, Monmouth, Otranto and Canopus made up the west coast squadron and rounded the Horn, with Canopus detached and following the other ships as best she might.

Meanwhile, on 30 October a new board of Admiralty had been appointed with Lord Fisher as First Sea Lord. They at once telegraphed to him that he was to keep his squadron concentrated and for reinforcement from Defence - and that he was not expected to fight without the Canopus. The new orders never reached him.

On October 29 Glasgow was sent to the port of Coronel in Chile, while there picked up radio transmissions between Leipzig and one of her colliers (the signals were warning von Spee of Glasgow's presence). The squadron was reformed and spread out to sweep north. On 1 November 1914 Good Hope, Monmouth, Glasgow and Otranto encountered von Spee's force: Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Leipzig and Dresden, with Nürnberg thirty miles to the north. These modern vessels were much superior to Cradock's force. Canopus was still 300 miles away to the south, escorting the squadron's colliers.

|

| Admiral Maximilian von Spee |

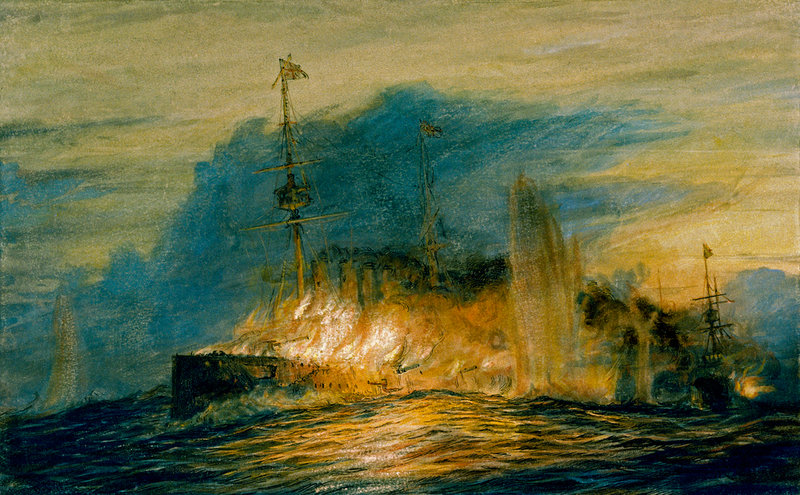

At about 1930 at 12,000 yards the German armoured cruisers opened fire, keeping their distance so as to stay out of the range of the British guns. The setting sun silhouetted the British squadron whilst the German ships were hard to see in the failing light. The third salvo from Scharnhorst hit Good Hope, knocking out her forward 9.2 inch gun. Monmouth was also hit by the third salvo from Gneisenau, setting her forward turret on fire. The visibility deteriorated so that the Germans had to target the fires on the British ships whilst the British had to make do with aiming at the enemy gun flashes. Leipzig and Glasgow engaged each other whilst Dresden fired on Otranto which rapidly pulled out of the line and fled, enabling Dresden to also engage Glasgow. At 1950 Good Hope suffered a magazine explosion, the crippled ship then drifting out of site and sinking soon afterwards. There were no survivors.

|

| 'Rear Admiral Cradock's flagship, HMS Good Hope on fire', by W.L. Wyllie |

Monmouth was also on fire and listing to port. Glasgow had been hit five times and seeing that Monmouth was beyond help fled to avoid certain destruction and to warn Canopus to turn back. Nürnberg , ariving on the scene finished Monmouth off with gunfire at point blank. Again there were no survivors.

Within two hours the British had lost two battle cruisers and almost 1,600 men, including Admiral Cradock. The only damage to the Germans was two hits on Scharnhorst and four hits and three wounded on Gneisenau.

In response to the first major defeat suffered by the Royal Navy in over 100 years, and in answer to the continuing threat from von Spee's ships, a substantial new squadron was put together under the command of Vice-Admiral Doveton Sturdee (ironically as a demotion from a staff position following the changes at the Admiralty). On 8 December 1914 von Spee, low on coal and having used half his ammunition at the Battle of Coronel, arrived at the Falkland Islands only to find Sturdee waiting for him. In the ensuing battle, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Nürnberg and Leipzig were all sunk and von Spee and almost 2,200 German sailors killed.

|

| Arthur Balfour (foreign secretary) unveils the memorial to Admiral Cradock at York (Click on link for movie) |

- Royal Victorian Order, Member (MVO), 1903; Knight Commander (KCVO), 1912

- Order of the Bath, Commander (CB), 1902

- Queen Victoria Diamond Jubilee Medal

- Edward VII Coronation Medal

- George V Coronation Medal

- China War Medal, 1900 (two clasps: Taku Forts and ?)

- 1914-15 Star (not in photo)

- British War Medal (not in photo)

- Victory Medal (not in photo)

- Sea Gallantry Medal

- Turkish Order of the Medjidie

- Khedive's Star (clasp Toker)

- Prussian Order of the Crown (with swords)

- Spain Order of Naval Merit

'to him the navy was not a collection of ships, but a community of men with high purpose'.

ReplyDeleteInteresting. A nation can buy/build ships but can they crew them. A problem that is very contemporary.

cheers